Oggi vorrei portare alla luce un saggio rivoluzionario, fonte di ispirazione per moltissimi scienziati che hanno contribuito all’innovazione tecnologica, soprattutto nell’informatica degli anni a seguire.

Questo saggio, venne scritto nel 1945 da Vannevar Bush, pubblicato dalla rivista The Atlantic Monthly ed introdusse la scienza verso un nuovo modo di concepire le cose, mettendo in chiaro che per anni, tutti quante le invenzioni hanno solo preso in considerazione l’estensione dei poteri fisici dell’uomo, piuttosto che i poteri della sua mente.

Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush è stato un ingegnere americano, nato l’11 marzo 1890, vicepresidente dell’MIT e detentore di molti brevetti sui computer analogici, oltre ad essere stato l’inventore dell’analizzatore differenziale.

Dal 1945 diresse l’Ufficio della Ricerca e lo Sviluppo scientifico degli Stati Uniti D’America, quell’organismo che sviluppò numerose ricerche in ambito militare, come ad esempio il radar, oltre che al controllo del Progetto Manhattan, quel progetto che permise la produzione delle prime bombe nucleari.

Scrisse nel 1945 un saggio dal titolo “As We May Think” che venne pubblicato a luglio dalla rivista The Atlantic Monthly, oltre che essere ripubblicato in una versione più ridotta nel settembre dello stesso anno, praticamente a cavallo dei bombardamenti di Hiroshima e Nagasaki .

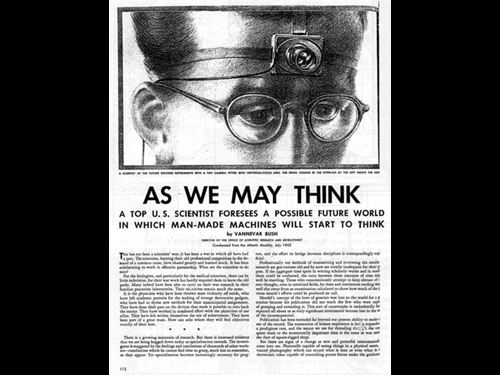

Copertina del saggio “As We May Think”

Bush esprimeva la sua preoccupazione per la direzione degli sforzi scientifici verso la distruzione di massa, piuttosto che verso la comprensione, e spiegò il desiderio e la necessità di una sorta di – macchina della memoria collettiva – con l’enorme potenziale di rendere la conoscenza più accessibile a tutti, oltre a rispondere alla domanda

“Come può la tecnologia contribuire al benessere dell’umanità?”

Il saggio fonda il ragionamento su una premessa: la conoscenza umana è un insieme di conoscenze collegate e ha una dimensione universale che non può essere limitata alla vita del singolo.

Il sapere è frutto di un processo continuo, costruito grazie ad una proficua collaborazione tra gli scienziati ed include il patrimonio di tutte quelle conoscenze umane, dove l’accesso all’informazione scientifica è una condizione necessaria per la crescita del genere umano.

Infatti non si trattava di una mera questione tecnica, l’argomento del saggio era per lo più una forte riflessione filosofica e politica su come si produce e si comunica il sapere.

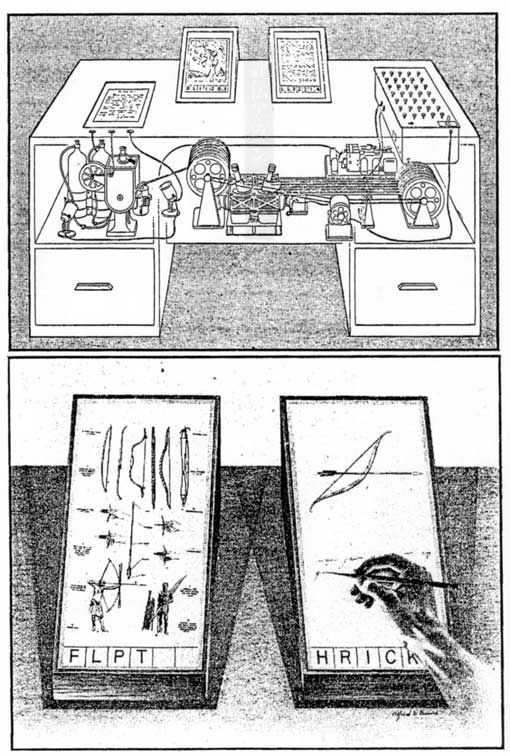

Bush, nella sezione 6 delle 8 presenti nel saggio, presenta il “memex”, una sorta di estensione della memoria umana sotto forma di una scrivania meccanica che conteneva al suo interno un archivio a microfilm, che di fatto sarebbe stato il supporto di archiviazione per immagazzinare libri, registri e documenti per poterli successivamente riprodurli ed associarli gli uni agli altri.

Il Memex in alto e i due schermi in basso.

Il memex prende appunto il nome da “memory extender” e risulta essenziale in quanto Bush dice che

“La mente umana Opera per associazione. Con un oggetto in mano, scatta istantaneamente a quello successivo suggerito dall’associazione dei pensieri, in accordo con una intricata rete di tracce trasportate dalle cellule del cervello”

Il memex infatti aiuta il ricercatore a ricordare le cose più rapidamente, oltre a poter velocemente vedere i propri archivi di informazioni digitando il codice del registro e del libro, in modo da poterlo richiamare e visualizzare immediatamente su uno dei suoi visori.

L’interfaccia era semplice, costituita da pulsanti e semplici leve.

Spostando la leva a destra si passa alla pagina successiva, mentre spostandola ancora di più sulla destra, il memex scorrerà 10 pagine alla volta, ovviamente spostandola a sinistra, avrà la stessa funzionalità ma al contrario, mentre un apposito pulsante consente il riposizionamento alla prima pagina del libro.

Inoltre l’utente del memex avrebbe potuto aprire più libri contemporaneamente, magari sullo stesso argomento, di fatto creando un percorso e dei collegamenti tra le informazioni, definendo di fatto un nuovo libro, oltre che prendere appunti grazie ad una tecnologia di fotografia a secco.

Bush con questo saggio, anticipa fortemente quello che successivamente vedremo qualche decennio dopo sul world wide web, oltre a rivoluzionare il concetto di postazione di lavoro introducendo la navigazione pagina per pagina tramite collegamenti e link.

Questo saggio ispirò in modo fondamentale le successive innovazioni dell’oN-Line-System, il sistema operativo creato da Dug Engelbart, presentato nella “Mother of all demos” del 1968 del quale abbiamo parlato in un precedente articolo su Red Hot Cyber.

Fonti

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Ne stiamo discutendo nella nostra Community su LinkedIn, Facebook e Instagram. Seguici anche su Google News, per ricevere aggiornamenti quotidiani sulla sicurezza informatica o Scrivici se desideri segnalarci notizie, approfondimenti o contributi da pubblicare.

Cybercrime

CybercrimeLe autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si concentra su profili specifici, tra…

Innovazione

InnovazioneL’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “Meatspace Layer”: un’infrastruttura dove le macchine non…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNegli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’analisi recente ha portato alla luce uno…

Vulnerabilità

VulnerabilitàNegli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici e veloci. Con pochi click…

Innovazione

InnovazioneArticolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i vari payload multisensoriali, meno…