Author: Massimiliano Brolli

Original Publication Date: 12/12/2020

Translator: Tara Lie

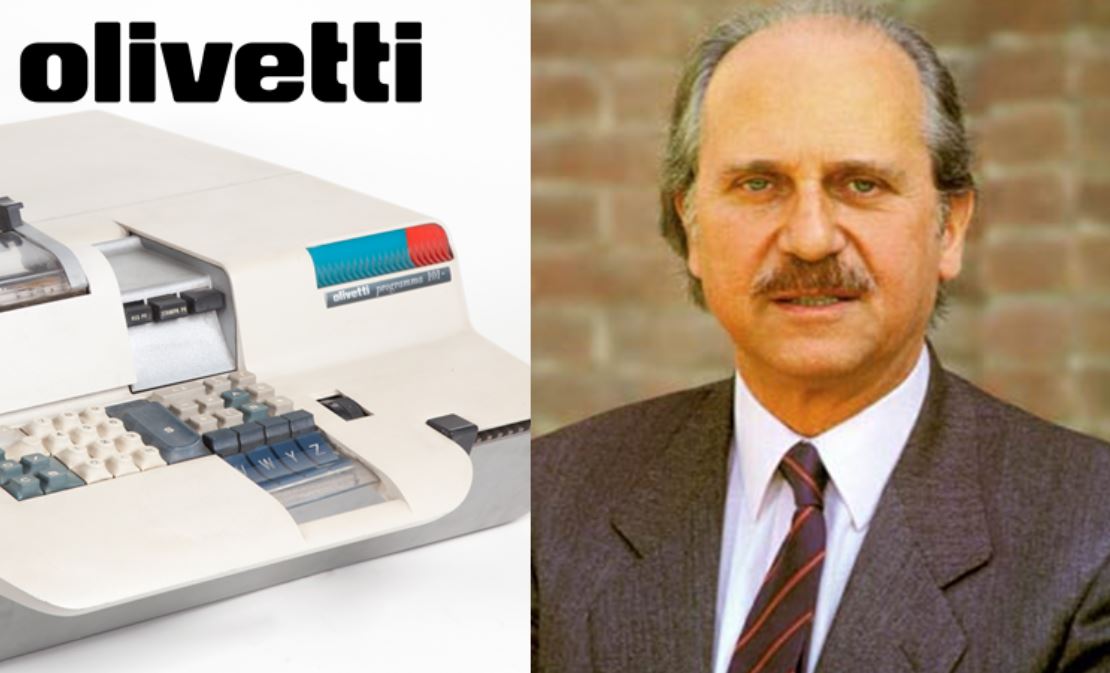

Pier Giorgio Perotto (for those who do not know of him) was an Italian electronics pioneer. In the 60’s he worked for Olivetti, and led the team that built the Olivetti Programma 101 (P101), the first desktop computer in history.

The P101, also known as the Perottina, was launched at the 1964 New York World Fair, and was even used by NASA to plan and calculate the space program’s orbits, including the Apollo 11 mission that took man to the moon.

For those who would like more details on the Olivetti Programma 101, you can watch the video on the Red Hot Cyber YouTube channel.

This article will discuss a piece of Perotto’s book “Programma 101”, written in the 2000’s, which tells a fascinating story and commentary on innovation in Italy.

Although many years have passed since Perotto wrote this book, inside we find a synthesis of interesting and still-current passages on why Italy is a country of ‘unarmed innovators’ who struggle to emerge due to the lack of foresight of a country that prefers the logic of imitation, with the propensity to want to be a perennial “followers” of overseas technology, rather than “influencers” of the international geopolitical scene.

Is it possible to create a revolutionary new electronic product in a company that doesn’t want to know about it, and that instead makes its strategy to reject electronics in favour of the limits of traditional mechanical technology? In Italy it is possible, and this is what happened in Olivetti during the 60s.

The product of which we speak is the personal computer, otherwise called the Perottina: at least, these were the terms coined for the external and internal use in the company. The reasons why the case of the invention of the PC is worth remembering are not only to reaffirm an Italian world priority or to retrace a lamentable bitterness, but also to draw lessons from it in order to understand and address the current problems of our country’s poor capacity for innovation. This is a crucial limitation, which persists, and will condition our next development.

Italy is not, today as in the past, affected only by a kind of idiosyncrasy or horror vacui regarding research (for which we are at the bottom of the list of industrialised countries, as the ratio of investment to GDP) but above all by an industrial culture that abhors the idea of running the risks associated with the opening of new sectors.

Unfortunately, we are now in a historical period in which the foundations of the global information society are being built, and the opening of new sectors is precisely the most typical event and precursor of revolutionary innovations. However in Italy, innovators – as unarmed prophets – continue to have a hard life. Particularly in large companies, the dominant culture is that of slavish imitation of overseas fashions and resignation. Relatedly, Italian entrepreneurship suffers from a syndrome that leads it to privilege the follower strategy, a sort of chauvinism-in-reverse.

The events that occurred at Olivetti thirty years ago are paradigmatic, and therefore it is worth summarising them. The year is 1961. Olivetti as a company is still recovering from the sudden death of Adriano Olivetti, and on the horizon there are signs of an economic recession with which the decade of the economic miracle is coming to an end.

The company is engaged in two adventures, both endorsed by Adriano: the development of the Electronics Division to design and produce computers, and the merging of Underwood, an American company acquired to conquer the North American market. However, neither of the two operations was shared by the establishment of the company, accustomed to the profits derived from the great worldwide success of Divisumma 24, a calculator designed by Natale Capellaro (a brilliant mind and worker, discovered by Adriano Olivetti and appointed by him general manager).

While, however, the acquisition of Underwood had a mixed reception (although in retrospect it proved to be a disastrous operation) because it did conform to a certain normal policy of commercial expansion in the traditional sectors of the company, what did not go well with the conservatives was the advancement of electronics, at the time seen as a dangerous and uncertain sector. It is said that the idea of designing computers came from Enrico Fermi and was formulated on the occasion of his visit to Italy in 1949, during which he met Adriano Olivetti

Inversely, I believe that Olivetti fell in love with the idea because he saw in computer science a role of regulating and creating a superior aesthetic order in an immaterial field such as information, as well as urbanism and architecture are in the design of cities. But Adriano Olivetti created a block, which instead of enjoying the support and esteem of the industrial establishment, drew hostility and distrust upon it.

The result was that, upon his death, the electronics operation of Olivetti entered a crisis that I could not say whether it were more ideological or financial, a crisis that affected the entire company. I had the fortune to be a direct witness of the dramatic story, which ended in 1964 with the unfortunate renunciation and sale of the entire electronic sector to General Electric. One of the researchers was recruited for the Pisa electronic research laboratory, the first establishment dedicated to this new technology. The transfer of the Olivetti Electronic Division matured – tragically coinciding with the start of the world microelectronics revolution – due to the determination of the strong powers of finance and national industry to kill the initiative, and utterly indifferent political forces.

I perfectly remember a statement by Professor Valletta (President of Fiat and inspirer of the intervention group that at the beginning of 1964 took the reins of Olivetti) on the crisis:

“The company Ivrea is structurally sound and will be able to overcome the critical moment without great difficulty. However, a threat hangs over its future, a mole to be eradicated: being part of the electronic sector, for which we need investments that no Italian company can face”.

It did not take long to understand, when the new management took control, what the fate of the electronics would be. Nothing official was said, but the strategy was that of a general relaunch of all mechanical products; and the thing was thought of to be in great style, organising a presentation at the international exhibition of products for the office, in October 1964 in New York.

In the meantime, the electronics division was quietly sold to General Electric (G.E). It was said that the operation and the consequent collaboration with the G.E. would be used to deliver Olivetti the fruits of the great American research laboratories, that the Olivetti electronics did not die and that in the future it would benefit; however they all realised that it was a misrepresentation.

And above all I realised myself that, having participated in the negotiations and working in the electronic laboratories ceded to the Americans (of which I could test the arrogance and their exclusively commercial intentions) I had the opportunity to know the real reasons for the operation. For this reason I had the unfortunate idea, as a young naive, to contest the sale, obtaining the result of myself being returned by the Americans to Olivetti, with a plea to get out of the way.

Many think with reverence about Strategy as a noble activity in which the future destiny of a company is decided. In this specific case, the fate of Olivetti was decided by the non-strategy! I’ll explain myself better. My return to Olivetti after my expulsion allowed me to dedicate myself to one of the research activities that companies usually carry out in complete indifference: to explore the future possibility of building office products with electronic technologies.

This then seemed all the more far-fetched and improbable, since in the 1960s there were only large computers operating in data centres, far removed from the world of offices, and no reasonable person thought that you could make electronic machines of such a size and cost to fit on a single individual’s desk. I was then confined with some coworkers into a small laboratory in Milan, in the territory of the G.E., because if the Americans were disliked, the environment in Ivrea, the temple of mechanics, was not much better.

But this time the intervention group, which had staked everything on the relaunch of mechanics, was really unlucky, because a “small, big idea” unexpectedly sprouted in my laboratory: that of the personal computer (preceding the PC introduced in America by ten years!). I do not want to discuss the dramatic events that led to this result here (and I refer to the book of which this article is a summary). But the embarrassment and indifference with which the new management accepted the news of the unexpected epiphany at least had the merit of leading to a timid, but positive, decision: to expose the new machine, as a pure demonstration model, in a private room of the New York exhibition. What the strategy did not do, was the guilt complex linked to the sale of electronics and the desire to show that Olivetti in the end did do something exploratory with electronics, despite not believing us.

However, what happened at the World Fair was extraordinary and shocking: the American public perfectly understood what the company’s management had not, namely the revolutionary value of the “Programma 101”; treating the mechanical products on show with absolute indifference and instead sitting in the private room to see what the new product was able to do. The press, technical and otherwise, marked the success of the presentation with enthusiastic articles. In practice, the new computer was literally sucked out of the market: you can say that it was not sold, it was just bought!

What lessons can we draw out for the present day?

The New Economy that is emerging in the world around the network of networks today allows innovators to create companies based only on the strength of an idea. In 1964 this was not possible, but through the web, the thresholds to overcome to create a new business have now been drastically lowered. We even have individuals who dare to challenge the world giants of computer science (see the case of the Finnish student Linus Tordvald, who challenged Microsoft with his Linux operating system). Additionally, I also have the impression that today inventors can not only not die poor, but even climb the world rankings of the super-rich.

Another lesson that can be drawn from the case of the “Program 101” (a case that is in fact used in Harward’s MBA courses) is that of discontinuity management, which represents increasingly frequent situations in contemporary society.

Gone are the times when the future could be extrapolated from the events of the past. In the field of technology, but also in the world of applications, innovations represent breaks with the past: the new technologies operate as killers of the traditional ones, and constitute the base of new paradigms; and companies that know how to exploit them rarely find themselves among those leaders of old.

In fact, the leadership of Olivetti in the mechanics of computers and typewriters had turned off their ability to hear the faint warning signals of the upcoming microelectronics revolution that would soon transform the world.

If the small group of rebellious designers of the “Programma 101” did not have the strength and courage to affirm the potential of new technologies (and then become the architect of the great mutation of the company, from mechanics to electronics), the company would have achieved the same end in the 60’s as many prestigious names in computing and other office products – disappeared and no longer resurrected.

Finally, I hope that the story of the “Programma 101” will help motivate many young people with creative abilities to be daring and to take risks, without being conditioned by the common-thinking of the moment. In our country, in too many cases, there are the bearers of that culture of resignation and timidness, which runs the risk that our national system will remain excluded from the fascinating task of building the society of the 21st century.

I would also like this article, and the book of which it is a synthesis, to be perceived as a tribute to the figure of Adriano Olivetti, an enlightened and misunderstood entrepreneur who was a forerunner of the times.

___

It has been a long time since Perotto wrote this book, but many things still seem current. Adriano Olivetti also said:

“Italy is still progressing in compromise, in the old systems of political transformation, of bureaucratic power, of great promises, of great plans and modest achievements”

But we hope in future that all this will change quickly.

Follow us on Google News to receive daily updates on cybersecurity. Contact us if you would like to report news, insights or content for publication.