Tara Lie : 22 February 2024 18:25

Original Publication Date: Massimiliano Brolli, 25 September 2021

Today, exchanging a message through WhatsApp or Skype is a normal gesture, part of the activities we carry out in our daily lives. In all the history books, it is reported that on the evening of July 20, 1969 at 20:17, Neil Armstrong, after setting foot on the moon said the famous phrase:

“One small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

But on the evening of Wednesday, October 29th that same year at 10:30pm – practically three months later – there was another great leap for mankind, perhaps even more important than Armstrong’s. This leap however is not often mentioned in the history books.

That evening, the first message was sent in a computer network, and that is what we will discuss in this article.

Los Angeles, UCLA University

California, Los Angeles, UCLA University – 29th October 1969.

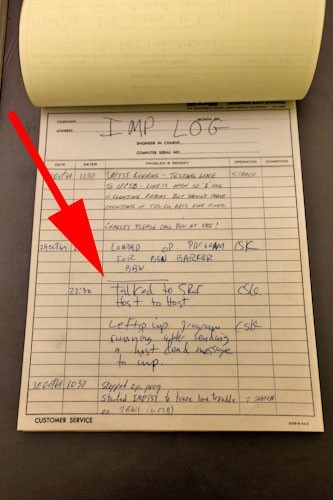

That evening, UCLA Professor Leonard Kleinrock and his student Charley Kline sat in front of the SDS Sigma 7 computer, ready to send a message. The message was destined for Bill Duval, standing in front of an SDS 940 at Stanford University 350 miles away, through the brand new internetwork sponsored by the Advanced Research Projects Agency – known to all as ARPANET.

Everything was ready, the computers were fully functional.

“Okay Stanford, we’re about to send the letter L, let us know when you see it’, Kleinrock said to Stanford.

“There it is, got the L” came the reply. UCLA heard a round of applause in the background from the receiver.

“Okay, very very good, just a second, we’ll send the letter O”, Kline said from UCLA to Duval at Stanford.

“Oh my God, we just got an O, keep going.”

“Get ready, here’s a G coming, let me know when you’ve got it”. But then, a few seconds passed before Duval said “Did you send it?”

“Yeah, we just sent the G, have you got it?” the reply came from UCLA, but a few more seconds passed in silence.

“Damn it, the 940 has just crashed” came from Stanford.

“Who cares, we did it, it’s a success! Bring out the champagne!”

About a half hour later the computer scientists tried the test again and were able to transmit the word “Login”.

The evening of October 29th 1969, the first message was sent between two computers, which was a very important advancement for the history of technology and electronics. These computers had significantly lower performance abilities than a simple smartphone today – in the realm of 129KB if RAN and 24 MB of disk space.

This was in the “Jurassic” period of computer science, the era of great innovation and scientific research, but also of great hackers and computer science pioneers who laid the foundations of the modern internet and of every piece of technology that surrounds us today in our daily lives.

The 3420 Boelter Hall at UCLA.

It is clear that the first message in a network between computers was the arrival point of a long journey, carried out in the design and implementation of a network that starts from even further back. In fact, it was the American president Eisenhower, terrified that America might lose its scientific advantage, who gathered the best scientists of the time around him by appointing James Killian as Head of ARPA – the Advanced Project Research Agency.

It was then that the military and academics, in the midst of the Cold War, developed a military network capable of resisting nuclear attack together. They also worked together to allocate human and financial resources dedicated to scientific research in the best way, thanks also to the collaboration at all levels including also companies. Although, it was the academics who were those to theorise, design and develop the network.

In 1967, Lawrence Roberts, as program manager, began to theorise ARPANET by using packet switching techniques invented by British computer scientist Donald Davies and the American Paul Baran. Once the design was completed, ARPA issued a Request for Quotation to build the system, which was assigned to Bolt, Bèranek, and Newman – the famous BBN technology. Their company contributed to the birth of the internet in a fundamental way, by designing the routing, flow control, software design and network control. Lawrence Roberts managed the implementation of ARPANET and in 1968 asked Leonard Kleinrock to perform the mathematical modelling of packet switched network performance such as “queue theory”, a branch of research which has applications in many fields.

What happened on the evening of the 29th of October 1969 was the end of a journey, but all masterpieces come to life after intense and meticulous work beforehand.

To speak about this today is similar to talking about a past geological era, when dinosaurs roamed the Earth, even though we’re are only referring to little over 50 years ago. If we were to think about today’s technology in that era, what would come to mind? On that day, probably, other than the first message sent in a computer network, Denial of Service (DoS) was born, without the academic world being aware of it, but that is a whole other story…..

Tara Lie

Tara Lie