Autore: Jesse McGraw, alias Ghost Exodus

Data Pubblicazione: 11/06/2022

Apparentemente, i database dei registri pubblici del governo aiutano le forze dell’ordine a salvare vite umane, impedendo che altri crimini vengano commessi dagli autori di reati, fornendo allo stesso tempo anche una piattaforma informativa dettagliata che può mettere insieme i dati corretti che possono aiutarli a dare la caccia e catturare i fuggitivi e le persone in fuga da un mandato di arresto.

L’accesso a questi sistemi di registrazione pubblica è impostato per aiutare i professionisti legali a risolvere i casi più velocemente, riducendo il numero di persone che normalmente occorrerebbero per risolverli, nonché il tempo e le spese associate a lunghe indagini.

Non è raro associare le nostre idee su tali database con le immagini e le scene dei film, dai terminali testuali in bianco e nero alle interfacce altamente grafiche e sofisticate rappresentate nei film di spionaggio di successo.

In qualità di ex hacker, ho acquisito molta familiarità con i database delle forze dell’ordine come il Texas Law Enforcement Telecommunications System, International Justice and Public Safety Network, Bureau of Prisons Network, Legal Information Office Network System e il National Crime Information Center.

Tuttavia, esiste un gigante del data mining chiamato Accurint for Law Enforcement (Accurint LE) che non lascia nulla all’immaginazione.

Nel 2009 sono stato arrestato e accusato con due capi di imputazione per la trasmissione di un codice dannoso o installazione di malware, in pratica. Durante la detenzione/udienza per la cauzione, il procuratore che rappresenta il governo in questo caso mi ha falsamente accusato di possedere un kit di identificazione falso oltre ad affermare che avessi usato più false identità. Questa informazione era palesemente inesatta e divenne un fattore convincente che indusse il giudice magistrato a negarmi una cauzione. Dopo aver discusso questo problema con il mio difensore d’ufficio, ci siamo mossi per presentare una petizione al pubblico ministero per produrre prove a sostegno di questa affermazione.

Le informazioni fornite dal pubblico ministero provenivano da Accurint.

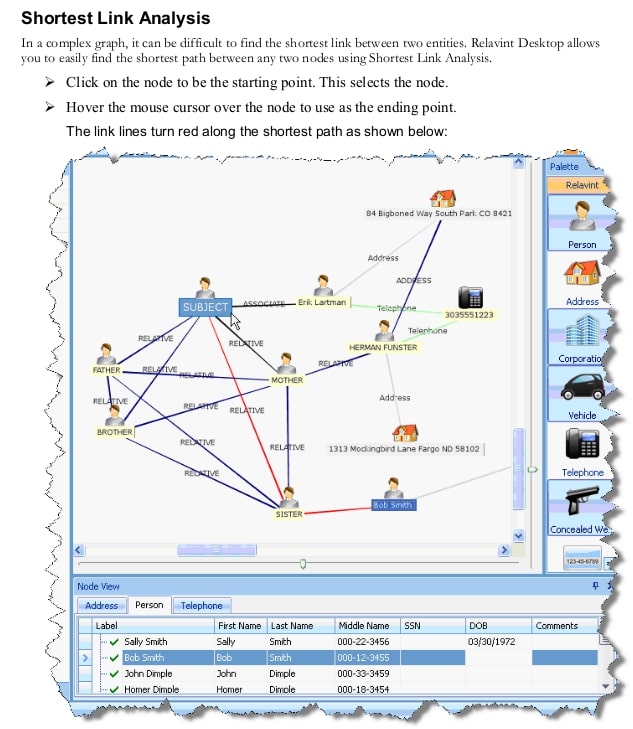

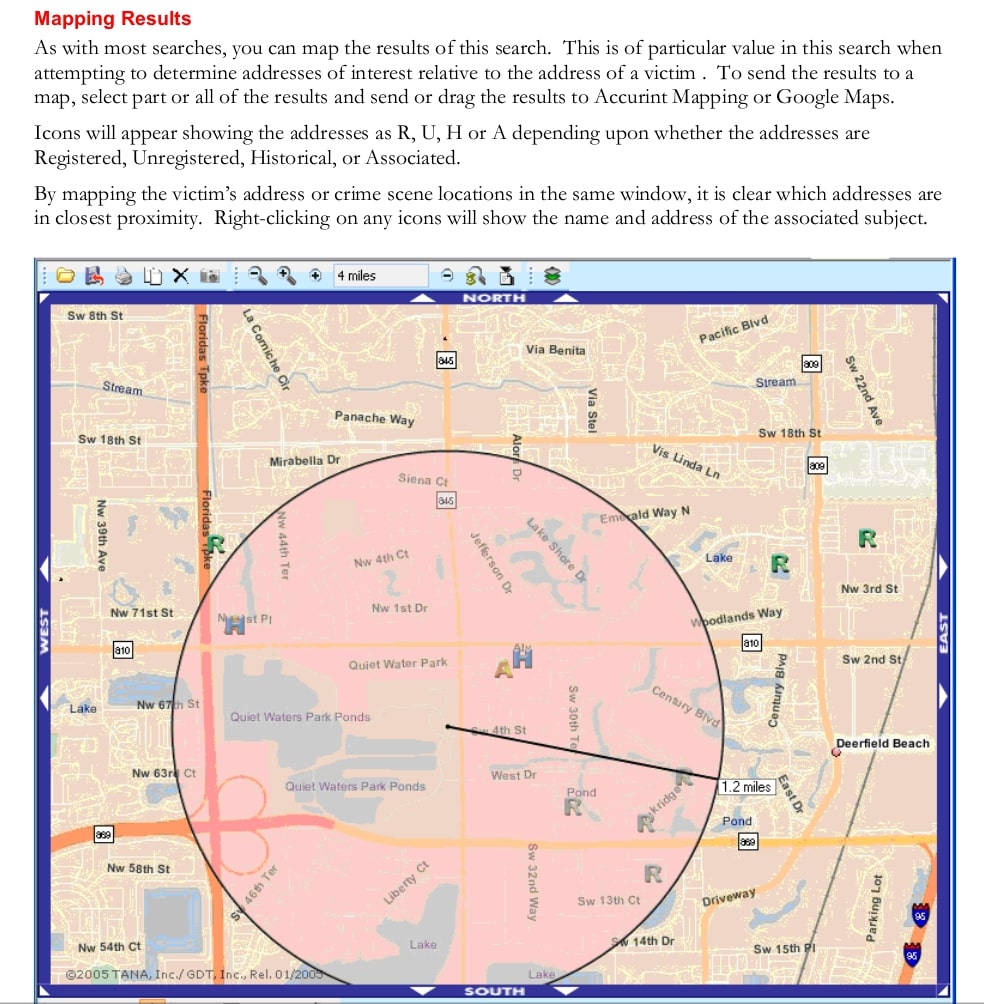

Accurint for Law Enforcement è uno strumento di ricerca sui registri pubblici ampiamente popolare ed estremamente esaustivo fornito dal broker di dati LexisNexis. Dispone di potenti funzionalità di tracciamento e mappatura delle persone che raccolgono le sue risorse da una moltitudine di banche dati utilizzando la tecnologia di data mining per far convergere le informazioni in un unico, enorme pool di informazioni centralizzato.

Può rivelare connessioni tra persone, aziende, risorse e luoghi che non possono essere trovati nei registri pubblici, anche se l’utente ha solo frammenti di informazioni sull’individuo che sta cercando.

Il database Accurint contiene 84 miliardi di record pubblici su 283 milioni di identità univoche, una media di circa 290 record per identità. Milioni di rapporti Accurint vengono venduti ogni anno ad agenzie governative, forze dell’ordine, compagnie assicurative, banche, collezioni e qualsiasi altra entità.

Esempi di alcuni dei documenti che Accurint può estrarre includono beni come proprietà, veicoli a motore, aeromobili della FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) e licenze per imbarcazioni, nonché le registrazioni delle armi da fuoco.

Può generare un albero informativo dettagliato delle relazioni tra gli individui e il luogo in cui vivono, come contattarli, registri di telefonia mobile e di rete fissa, immatricolazione di veicoli e rapporti di incidenti, precedenti occupazionali, chi sono i loro colleghi, le loro affiliazioni, precedenti penali nonché intricati dettagli sui loro comportamenti finanziari. Documenti di nascita. Rapporti di credito. Di tutto.

A quanto pare, l’intelligence investigativa non è mai stata così facile. Accurint LE può anche monitorare i social media, consentendo alle agenzie di scoprire rischi e minacce sfruttando i social media per fornire informazioni fruibili.

I clienti governativi, delle forze dell’ordine e commerciali sono tra i molti utenti del database e il costo per eseguire ricerche fulminee può ammontare a semplici spiccioli. È utilizzato da oltre 4.000 forze dell’ordine federali, statali e locali negli Stati Uniti

LexisNexis, l’acclamato gigante delle informazioni legali, normative, aziendali e di analisi e broker di dati che possiede i diritti dello strumento, descrive Accurint LE come “una tecnologia investigativa all’avanguardia che può accelerare l’identificazione delle persone e dei loro beni, indirizzi, parenti e soci in affari fornendo accesso istantaneo a un database completo di documenti pubblici che normalmente richiederebbero giorni per essere raccolti“.

Secondo la società,”assiste il 70% delle agenzie locali e quasi l’80% delle agenzie federali per salvaguardare i cittadini e ridurre le perdite finanziarie dovute a frodi e abusi”.

Hank Asher, meglio conosciuto come “il padre della fusione dei dati”, è il celebre creatore e genio informatico dietro questo impressionante titano di data mining e collegamento di dati. Non dovrebbe sorprendere che sia stato descritto da uno dei suoi dipendenti come uno “scienziato pazzo”. Altri lo considerano una sorta di leggenda.

Il danno causato dal mio rapporto Accurint era irreparabile. Il pubblico ministero ha inviato una stampa dettagliata di Accurint al mio avvocato, che poi me l’ha inoltrata in modo che potessi esaminare la fonte della richiesta del governo.

Il database riportava in modo impreciso che presumibilmente avevo più pseudonimi collegati al mio numero di previdenza sociale (SSN) riorganizzando e combinando le variazioni del mio nome di nascita e nome legale insieme al nome da sposata di mia madre. Erano nomi che non avevo mai usato.

Tuttavia, il danno era fatto e questa disinformazione era già stata ripetuta dai giornalisti dei media. Undici anni dopo e quelle stesse notizie si trovano ancora in tutto il web. Il disclaimer in cima ai record compilati da Accurint sembrava essere ignorato. In breve, ha affermato che le informazioni immesse in queste banche dati sono talvolta imprecise e che sono necessarie ulteriori indagini investigative. Immaginate.

Un altro esempio di informazioni imprecise fornite da Accurint è stato descritto in modo simile da Meghan Koushik, una ricercatrice associata al Brennan Center for Justice, che ha avuto l’opportunità di eseguire una ricerca con il suo nome nel 2014. Con la sicurezza di trovare poche informazioni dovuto al fatto di avere un nome univoco, non possedere la patente e in assenza precedenti penali, è rimasta scioccata dai risultati.

“… I rapporti elencavano ogni numero di telefono e indirizzo a cui ero stata associata, dalla cassetta della posta del college alla casa di un parente a cui avevo inoltrato la posta mentre ero all’estero. Accurint ha elencato l’appartamento che ho affittato durante un tirocinio a Washington, insieme ai nomi e ai numeri di telefono dei suoi attuali occupanti. Forniva persino il prezzo di vendita e il mutuo su ogni casa in cui avevo vissuto. Sorprendentemente, anche molte delle informazioni erano imprecise.

[…] Accurint elencava qualcuno di nome Florinda come “Associato al SSN” anche se mi ha assicurato che questo “di solito non indica una frode”.

Ha spiegato all’epoca che la modifica dei dati imprecisi si è rivelata impossibile perché i broker di dati non hanno consentito alle persone negli Stati Uniti di accedere e modificare i propri dati. C’è troppa burocrazia coinvolta e le modifiche alle informazioni spesso non vengono conservate in modo permanente.

Le informazioni vengono sottratte da una tale varietà di fonti che eventuali modifiche al rapporto di una persona verranno probabilmente sovrascritte man mano che il rapporto viene aggiornato.

Sembra che l’unica eccezione a questo problema sia riservata esclusivamente ai residenti dello Stato della California ai sensi del California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) che altrimenti si riservano il diritto di richiedere la cancellazione di determinate informazioni personali oltre a richiedere di non vendere le proprie informazioni personali .

Inoltre, le persone che non sono residenti nello Stato della California e che desiderano modificare le informazioni inesatte nel loro rapporto Accurint possono trovarsi davanti ad un processo uno sforzo scoraggiante e infruttuoso.

“Non esiste una legge federale generale sulla privacy che fornisca specificamente ai consumatori il diritto di scegliere se le loro informazioni possono essere raccolte e/o utilizzate o meno“, ha affermato Karen Gullo, parlando a nome della Electronic Frontier Foundation, organizzazione no profit che difende le libertà civili nel digitale mondo. “Una forte legislazione sulla privacy negli Stati Uniti è attesa da tempo. La legge sulla privacy dei dati della California è una legge statale che consente ai consumatori di conoscere ciò che le aziende raccolgono su di loro, eliminarlo e rinunciare alla vendita. Ma non dà ai consumatori il diritto di scegliere se raccogliere i propri dati“, ha agginto Gullo.

Michael Rapp, un avvocato di Kansas City, ha affermato che la sua azienda ha conteso dozzine di casi contro LexisNexis e alle aziende piace da più di un decennio. “Le persone possono aver danneggiata la propria reputazione da parte di aziende di cui non hanno mai sentito parlare e spesso non sanno fino a quando il danno non sarà fatto”, ha detto e ha continuato: “Questa è la cosa più grande di cui non sai nulla. È quasi impossibile evitare di essere rintracciati dai broker di dati, non solo da LexisNexis“.

Il rapporto di Accurint affermava che “potrebbe non contenere tutte le informazioni di identificazione personale nei nostri database” e “non verificano i dati, né è possibile modificare dati errati”. Un’affermazione come questa dovrebbe far girare la testa quando si tiene conto dell’entità della quantità di dati raccolti sui privati cittadini.

Per anni, LexisNexis ha venduto Accurint senza rispettare il Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) federale, sulla base della teoria secondo cui Accurint non è un “Consumer Report” che attiva le protezioni della legge. Nel 2013, LexisNexis ha risolto una causa collettiva da 13,5 milioni di dollari intentata da 30.000 querelanti che accusavano la società di aver raccolto i dati per venderli ad esattori che utilizzano i rapporti Accurint come strumento di skip tracing per rintracciare i consumatori, erano “Consumer Reports” come definito nell’FCRA.

Nel 2019, un altro caso di abuso ha coinvolto l’ex agente di polizia di Alice Enrique Saenz, oggetto di un’indagine dell’FBI sull’uso improprio di Accurint. La città di Alice è stata informata dall’FBI che Saenz stava usando il suo accesso ad Accurint da parte delle forze dell’ordine per perquisire illegalmente individui che non avevano alcun collegamento con un caso delle forze dell’ordine, qualcosa che potrebbe ricordarci i casi in cui almeno una dozzina di dipendenti della National Security Agency sono stati catturati utilizzando gli strumenti di sorveglianza della NSA per spiare le e-mail o le telefonate dei loro coniugi e amanti attuali o precedenti.

In realtà hanno un nome per questo: “LOVEINT” alias interesse amoroso, che è definito come la pratica dei dipendenti dei servizi di intelligence che utilizzano le loro ampie capacità di monitoraggio per spiare il loro interesse amoroso o il coniuge.

Come membri di una società globale, siamo suscettibili all’abuso arbitrario delle informazioni estratte e utilizzate dal governo e dalle forze dell’ordine? È difficile credere che qualcosa di simile possa mai influenzare i cittadini comuni come te e me, dal momento che non siamo informati o consapevolmente interessati su come vengono utilizzate le nostre informazioni personali, chi le sta usando, chi le vende e chi lo sta comprando. È allarmante?

Considerate questo, in circostanze normali, come durante un procedimento legale, dobbiamo firmare una rinuncia e fornire una conferma orale per rinunciare a un diritto costituzionalmente tutelato. In altre parole, dobbiamo partecipare attivamente alla questione direttamente affinché la rinuncia sia legalmente autenticata e quindi vincolante.

Sembra un po’ egoistico dopo aver esaminato le forze che controllano ciò che non è più nostro e considerato il fatto che noi cittadini non abbiamo autorità legale sulle nostre informazioni personali e nessuna protezione legale affidabile per difendere il nostro interesse alla libertà civile contro le società e il governo entità che stanno prendendo le nostre informazioni mentre noi guardiamo dall’altra parte a favore della “sicurezza nazionale”.

Quindi, la domanda rimane: la sicurezza è più importante della privacy?

A volte mi chiedo perché così tanti di noi sembrano pensare solo in termini binari come se potessimo avere solo uno senza l’altro. La domanda che dovremmo porci è se l’esistenza di tali potenti database di registri pubblici abbia avuto un effetto sul calo significativo del tasso di criminalità americana.

Se la risposta è sì, allora forse sarebbe prudente sollecitare i legislatori a creare leggi che tutelino l’interesse del pubblico i cui registri vengono altrimenti utilizzati senza il loro consenso. L’accesso alle nostre informazioni dovrebbe essere libero e la modifica di informazioni inesatte non dovrebbe mai diventare impossibile per nessun motivo.

Ma cosa accadrebbe se strumenti come Accurint LE non avessero avuto alcun effetto sul calo dell’attuale tasso di criminalità? Se è così, non dovrebbe esistere affatto, visto che le forze dell’ordine sarebbero in grado di produrre gli stessi risultati senza di esso come potrebbero con esso?

“La linea di fondo è che dobbiamo richiedere alle società private che raccolgono, utilizzano, conservano o condividono informazioni su di noi, comprese le nostre impronte o altre informazioni biometriche, di ottenere il consenso informato di attivazione prima di farlo e di ridurre al minimo i dati che elaborano a ciò che è necessario per dare ai consumatori ciò che hanno chiesto. E dobbiamo dare ai consumatori il diritto di intentare le proprie azioni legali contro le aziende che non lo fanno”, ha affermato Gullo.

Alcuni arrivano addirittura a dire che niente di tutto questo ha importanza. Non hanno niente da nascondere. Ma considerate questo.

Nelle parole di Edward Snowden, contractor della NSA e informatore di fama mondiale:

“Sostenere che non ti interessa il diritto alla privacy perché non hai nulla da nascondere non è diverso dal dire che non ti interessa la libertà di parola perché non hai niente da dire”.

Questo pezzo è stato scritto da Jesse McGraw, alias Ghost Exodus, fondatore dell’Electronik Tribulation Army. È un attivista, scrittore, ex hacker black hat e prima persona nella recente storia degli Stati Uniti condannato per corruzione dei sistemi di controllo industriale. Ana Alexandre ha contribuito a creare il reportage per questa storia su Forklog.

Leggi anche l’intervista a Jesse McGraw, alias Ghost Exodus su RedHotCyber

Ti è piaciuto questo articolo? Ne stiamo discutendo nella nostra Community su LinkedIn, Facebook e Instagram. Seguici anche su Google News, per ricevere aggiornamenti quotidiani sulla sicurezza informatica o Scrivici se desideri segnalarci notizie, approfondimenti o contributi da pubblicare.

Cybercrime

CybercrimeLe autorità tedesche hanno recentemente lanciato un avviso riguardante una sofisticata campagna di phishing che prende di mira gli utenti di Signal in Germania e nel resto d’Europa. L’attacco si concentra su profili specifici, tra…

Innovazione

InnovazioneL’evoluzione dell’Intelligenza Artificiale ha superato una nuova, inquietante frontiera. Se fino a ieri parlavamo di algoritmi confinati dietro uno schermo, oggi ci troviamo di fronte al concetto di “Meatspace Layer”: un’infrastruttura dove le macchine non…

Cybercrime

CybercrimeNegli ultimi anni, la sicurezza delle reti ha affrontato minacce sempre più sofisticate, capaci di aggirare le difese tradizionali e di penetrare negli strati più profondi delle infrastrutture. Un’analisi recente ha portato alla luce uno…

Vulnerabilità

VulnerabilitàNegli ultimi tempi, la piattaforma di automazione n8n sta affrontando una serie crescente di bug di sicurezza. n8n è una piattaforma di automazione che trasforma task complessi in operazioni semplici e veloci. Con pochi click…

Innovazione

InnovazioneArticolo scritto con la collaborazione di Giovanni Pollola. Per anni, “IA a bordo dei satelliti” serviva soprattutto a “ripulire” i dati: meno rumore nelle immagini e nei dati acquisiti attraverso i vari payload multisensoriali, meno…